The affair happened more than ten years ago. We worked together on a project with four other colleagues. She was married and had two small children …

Read the rest of this story in the Talking Soup Magazine.

"Write your way out of it." – J.D. Salinger

The affair happened more than ten years ago. We worked together on a project with four other colleagues. She was married and had two small children …

Read the rest of this story in the Talking Soup Magazine.

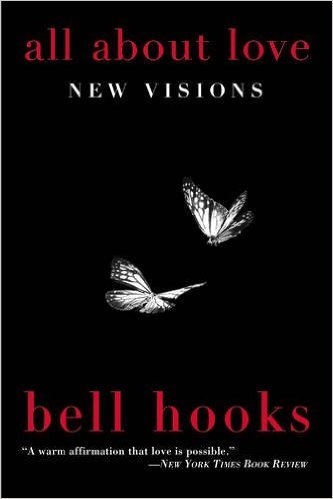

Many years ago, I ended my first book with a reference to the lyrics of Massive Attack’s song “Teardrop”: “Love is a verb, a doing word.” I make a habit of never re-reading my own work, but I was again reminded of that song while I was reading Bell Hook’s lovely treatise on the transformative power of love.

In All About Love: New Visions, Bell Hooks or—as in all her books, her name isn’t capitalized—bell hooks argues that love is what liberates us and others. She says it’s about time that we defined and understood love. For example, love is not something mystical, an excuse for losing all control, or—even worse—those times when we hurt someone out of love. Just imagine the parent who abuses his or her children yelling, “I hit you because I love you!”

“Love and abuse cannot coexist,” bell hooks says. I love her from saying so, with such argumentative strength that this is clearly non-negotiable.

In this way, hooks also lifts love from an individual to a social issue. We are formed by the society we live in. Therefore, unless we become conscious of our blind spots and fight to get rid of them, we might reproduce a misunderstanding of what love is and how to live and practice love.

“To maintain and satisfy greed, one must support domination. And the world of domination is always a world without love,” hooks writes. Just think of Trump. Is he alone the real problem, or is it the mentality or ideology that put him in power?

Hooks emphasizes that our current culture is full of greed and exploitation—not only sexual or gender exploitation but also racial and economic. She mentions how former president Bill Clinton’s sexual relationship with an intern exposed a fundamental flaw in his self-esteem and how easily such behavior was accepted or objections to it silenced.

Hooks offers us a useful definition of love that she takes from M. Scott Peck’s The Road Less Traveled. “Love is the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth.” In other words, love is not something that we simply activate by pushing a button. Rather, love is something we must learn. Important ingredients are care, trust, respect, affection, and honesty. Hook adds, “When we are loving, we openly and honestly express care, affection, responsibility, respect, commitment, and trust.”

As a parent, teacher, or adult, we are responsible to teach and cultivate love. This also means addressing situations in which we see love being violated, for instance, if some parents—or partners—use violence to express love. It’s not love. It’s violence and abuse.

“There can be no love without justice,” hooks writes. This means that parents and teachers should treat children with respect. My children are not my property. They are individuals that I have a responsibility towards, ensuring that each of them—with “them” being the operative word—is capable of giving and receiving love. This also illustrates the need to find the balance between setting limits and nurturing free expression. So, without justice, love can’t exist. It resembles Plato’s idea of the Good, which is right, just, and beautiful. Hooks is an idealist about love.

Hooks’s narrative is a mixture of a personal memoir, in which she refers to her own friends or relationships, and an ongoing dialogue with psychologists and spiritual thinkers. She has an especially critical outlook on sexist stereotypes that extend back to Eve and Adam, in which women, just by being females, were—or are!—less likely to tell the truth. After all, as the story goes, Eve did lie to God. However, who cares about this since God now is dead? I find that many care because, although we may not believe in any transcendent being, the idea still colors our culture and many people’s behavior.

Although I don’t mind setting love and freedom up as ideals—basically, because I can’t come up with any two virtues of more importance—I still think that hooks tends to moralize. Since I agree with her basic arguments, the challenge is to know when, or if, she takes her points too far. For example, she is apt to describe men as one homogenic mass, perhaps because of her stated agenda. She writes, “most men tend to be more concerned about sexual performance and sexual satisfaction than whether they are capable of giving and receiving love.” Here she falls for what is a stereotypical cliché, regardless of if this appears to fit scores of American men. Even in the United States, I believe that there are as many ways to be a man as there are to be a woman.

Basically, hooks describes men as rather primitive animals that hardly know how to show emotion, sounding like a popular journalist writing about Mars and Venus rather than grounding her discussion in facts. I have much sympathy for those wanting to get back at men, but this undermines her project since she doesn’t live up to her own philosophy. Love can only liberate us if we think beyond individual identity and experience. Even as I say this, I can’t help adoring bell hooks’ work. She also has written one of the best books on feminism, in which she stresses that men are not the problem but sexism and exploitation are.

For me, capitalism is the main evil and the cause of racial and gender inequalities. We all know that disparities and discrimination still exist. We know that a white patriarchal president at this moment reigns in the United States. We all know that he’s a racist and sexist who, I think, actually fears losing the fictional privileges he sees as due to him because of his gender and skin color. However, fortunately, far from every man is like him. I know I say this from a privileged position of being a Scandinavian brought up with a high level of equality (unfortunately, even Scandinavian countries now have a rising number in intolerant politicians and citizens), yet I also only need to look out my window here in Barcelona, Spain, to see that sexism, exploitation, and domestic violence are part of daily business.

I stand by hooks regardless of her stereotypical descriptions of men, and I am inspired by her overall idea that love should be first defined and then understood so that we can finally learn how to practice it. We can actively decide whether we really want to love this or that person. Believing this is impossible reduces humans to beings purely made up of lust and desire, whereas—as Spinoza said—we are a mixture of reason and emotions.

Thus, hooks advises us to stop saying, “I am in love,” and, instead, to say, “I am loving” or “I will love.” Emphasizing love as a verb and not as a noun requires courage. She writes, “as long as we are afraid to risk, we cannot know love.”

To love is to accept that no promises can be kept in life. All we can do is to live life to the fullest so that we, one day, can die without regrets. This echoes Plato’s idea that knowing how to live is also knowing how to die. As hooks might say, knowing how to love is also knowing how to die. I hereby warmly recommend All About Love.

In The Practice of the Wild, the poet Gary Snyder writes, ”The world is our conscious, and it surrounds us. There are more things in mind, in imagination, than ‘you’ can keep track of – thoughts, memories, images, angers, delights, rise unbidden.”

We are formed by the world. It resembles the mystery of our minds. Still, the world is suffering: Water shortage. Climate chaos. Mass poverty. Mass migration. Terrorism. Financial greed. And so forth.

What to do? In the same essay, Snyder stresses, ”An ethical life is one that is mindful.” Becoming mindful is the challenge.

Of course, we all know it. The world — our planet — needs our care to survive. Yet, it seems as if the planet is wrapped more in sweet and symbolic words than actual concrete actions. Saving the planet has become a moralistic quest. We have forgotten, “the shared ground of our common biological being,” as Snyder writes, that is to say; you have more in common with a lion than what differentiates you from it.

Saving the planet is our responsibility, some say. Some even wants to save it, because they feel guilty. They are concerned about the fear of suffering from future guilt, as when our kids or our friends kids confront us, “Why didn’t you do anything?” However, guilt, fear, and responsibility … I am not sure that it works. At least it doesn’t seem like it’s working. Instead, I suggest that we save the planet out of love.

It’s that simple. We need the planet because we love the sun, the rain, and the wind. We need the planet because we love how we are connected with every being that breathes. We need the planet because we live here; our memories, love stories and miseries are embedded here. We don’t love the planet because we need it for something as vague as career, status or prestige.

Out of love. That’s the best intention for everything. Out of love we plant small seeds, then we nurture them, take care of them, and we do so because deep down we know that survival of the fittest doesn’t rule the world (only capitalism works that way). On the contrary, in life it’s compassion, care, and love that rules. It’s because I care that some life will go on living.

Do you care?

An ethical life is mindful, well, a mindful life is one that tries to live here and now in our bodies. Here and now is also how Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari defined utopia in What Is Philosophy?, ”Utopia does not split off from infinite movement: etymologica1ly it stands for absolute deterritorialization but always at the critical point at which it is connected with the present relative milieu, and especially with the forces stifled by this milieu, Erewhon, the word used by Samuel Butler, refers not only to no-where but also to now-here.”

Utopia. Nowhere is always now and here. We don’t need more contemplation, not even higher ideals or moral categories. Rather we need to connect with the present. Becoming more mindful. Mindfulness of the body, for example, can be practiced by watching the breath when goes in and out, listening to the sounds, noticing the smells in the air, becoming aware of what we put in our mouth. Awareness is the key, not judgment. Mind and body are indistinguishable like Alberto Contador and his bike.

To love is not an intellectual project. Don’t your lips shiver when you kiss your lover? Do you love your kids out of responsibility? Out of guilt? No, because that’s not love. You love them because you love them.

Don’t you love the place where you live? If not … move to Mars.

For more on mindful philosophy, I have published the essay “Philosophy of Everyday Life” in the Journal of Philosophy of Life.