I’m pleased to announce that my new book, When life blooms – Breathe with Jeppe Hein will be released November 28th.

The publisher writes about the book:

“Danish artist Jeppe Hein soared to the top of the international art scene before the age of 35. His works were showcased at the world’s finest exhibitions and sold for sky-high prices. Then suddenly his body said stop. In 2009 Hein went down with stress.

In this book philosopher Finn Janning follows Jeppe Hein’s development from the tome immediately after his diagnosis with burn out and onward – a period where Hein underwent psychoanalysis and developed and interest in yoga, breathing exercises and spirituality.

Janning shows how spirituality has become more present in Hein’s works, and in the book, he develops an existential philosophy in continuation of the artists spirituality and art.”

I may add:

Although I was commissioned to write this book, I aimed at turning it into a philosophical biography that describes the life of the artist Jeppe Hein. In doing so, I’ve tried to exemplify Gilles Deleuze’s idea that “life is not personal,” that is to say, each life is a case study.

I choose this approach as a way of addressing the narcissism of the artist without making the narrative confronting, or in anyway judgmental.

Instead, I illustrate how Jeppe is formed by the major cultural trends during the last 40 years, such as the growing accelerating and spirituality and social entrepreneurship. He is an artist of his time.

It’s a book that tests and nuances the popularity of today’s spirituality through a philosophical, primarily existential lens.

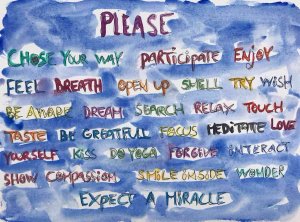

ENJOY